Airplane crashes often make sensational headlines in the news, yet thousands of them go mostly unnoticed by the media. Consider the count of fatal accidents in the United States during 2011. There were 285 investigations initiated by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), or about one crash every 30 hours (NTSB, 2013).

On 7 March 2013, one month ago, the NTSB published a factual report on the St. Ignace, Michigan accident of 3 December 2011. Amazon.com executive Thomas Phillips and his pilot were killed in this accident, which garnered national headlines in 2011. In contrast, there was only one article about the recent factual report in The Detroit News (Miles, 2013), plus an Associated Press article that appeared sporadically in newspapers such as the Wisconsin State Journal (“Bad Weather”, 2013).

I have followed this investigation since 2011 when I was coincidentally in contact with a relative of Mr. Phillips. I was not personally acquainted with Mr. Phillips, but I learned that he was a cousin-of-a-cousin to me.

While speaking with this common relative, I reviewed the NTSB preliminary report available at the time and explained my opinions:

- That the investigation would be a very long and potentially painful process from the family’s perspective.

- That the circumstances of the accident strongly suggested poor decision making by the pilot and the airline, which likely involved violating multiple Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR).

Nearly a year and a half later, the investigation is still ongoing. The factual report filed by the NTSB is a step in the investigative process that signals the completion of the information-gathering phase, and in larger investigations it incorporates the information produced by investigative committees. The cause of the accident has not been formally determined at this point. The NTSB will file a probable cause report to conclude the investigation, but that report is unlikely to contain any new information or surprising conclusions.

What the media fails to notice in this investigation is the opening of a public docket. Here exists an opportunity to analyze the available information in great detail and to try to answer more questions about what happened in 2011.

Preflight

In its 2013 report, the NTSB uses the term “accident pilot” to describe the pilot in command (PIC) of this flight and “other company pilot” to describe the employee who was in contact with the PIC prior to the flight. The other company pilot was also in contact with the passenger, Mr. Phillips, at 6 pm on 3 December 2011. The flight already had been delayed by bad weather, and this is where the accident story starts to get interesting.

This [other company] pilot stated he checked the [Mackinac Island] Automated Weather Observing System (AWOS) and it was reporting overcast clouds at 800 feet. He stated he told the accident pilot “don’t do anything dumb.” He then called the passenger and left a message stating that the weather now looked alright to get to the island. (NTSB, 2013, p. 1).

Which of the PIC’s preflight actions might have supported a decision to depart to an airport with an 800 ft ceiling? Did he obtain a preflight weather briefing? Such briefing was required for “a flight not in the vicinity of an airport” (Preflight action, 2011). This point was not addressed in the NTSB report, so there was no indication that the pilot was aware of prevailing conditions beyond what he was able to see on the ground and in the airplane.

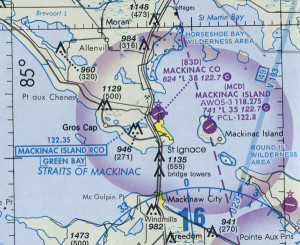

Did the pilot intend to operate under instrument flight rules (IFR)? According to both the preliminary report and the factual report, “Instrument meteorological conditions [IMC] prevailed and no flight plan was filed” (NTSB, 2013). The departure airport, St. Ignace, did not have the weather observation system that was required for an IFR departure (Weather reports and forecasts, 2011). Also, the airline president “stated that the accident airplane was strictly a VFR airplane” (NTSB, 2013, p. 1c).

The airline’s procedures allowed for dispatch of a flight without a flight plan only if the pilot could “maintain continuous communications with a ground facility” and the airline’s director of operations or director of maintenance were notified and on duty for the duration of the flight (Great Lakes Air, 2000, p. 35). Neither of these personnel was so notified, and the airline office was not staffed when the flight departed (NTSB, 2013, p. 1f).

Could the pilot legally operate by visual flight rules (VFR) under 14 C.F.R. § 135 with an 800 ft ceiling at the destination? Under the most liberal interpretation of Basic VFR weather minimums (2011) a VFR flight could have operated in the class G airspace if it remained 500 ft below the clouds. This was also allowed under VFR: Visibility requirements (2011). However, under VFR: Minimum altitudes (2011), no person may operate under VFR less than 1,000 ft above the highest obstacle within 5 miles. Both the departure and destination airports were within 5 miles of the 555-foot-tall Mackinac Bridge. The bridge would have reached within 500 ft of the ceiling, offering no possibility of flying 500 ft below the clouds and 1,000 ft above the obstacles. There are regulatory exceptions for operating lower for takeoff and landing, and for flying over open water. Did those exceptions make the flight legal? When asked about weather criteria, the airline’s president said, “We need at least 1,000 ft. ceilings” (NTSB, 2011, p. 3). Choosing to operate under these conditions was one example of poor decision making by the pilot and the airline.

VFR Flight into IMC

At the estimated time of departure from St. Ignace, 7:50 pm, the Mackinac Island AWOS reported the ceiling as 300 ft with 5 miles visibility, mist, and a dew point depression of one degree. Under these conditions, at night, over open water, it is unlikely the pilot could have seen the destination airport or seen any other visual reference outside the airplane. The pilot was essentially flying blind, or trying to navigate by instruments without an IFR clearance.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA, 2004) guidance on emergency procedures covers the topic of inadvertent VFR flight into IMC. The first steps toward surviving such an emergency are: Recognition, maintaining control, and obtaining assistance. “These situations must be accepted by the pilot involved as a genuine emergency” (FAA, 2004, p. 16-14). Whether or not the pilot recognized the situation as an emergency might never be known. The pilot did not attempt to obtain assistance. “There were no known communications between the airplane and any air traffic control facilities” (NTSB, 2013, p. 1d).

According to the Michigan Department of State Police, “Toronto Center … showed the plane take a course to the west, fly over Mackinac Bridge, then toward the Island. The signal was lost NE of the Island” (MSP, 2011, p. 3).

Flight Into Terrain

At the estimated time of 8:10 pm, the airplane carrying Mr. Phillips and his pilot crashed 1.6 miles north of the St. Ignace airport (NTSB, 2013, p. 1d).

Search and rescue operations began at 9:55 pm (MSP, 2011, p. 1) after the pilot’s wife reported him overdue.

A U.S. Coast Guard helicopter crew located the airplane wreckage at 11:50 am the next day (MSP, 2011, p. 5).

Terrain at the crash site was approximately 1,000 ft below the published VFR maximum elevation figure, 1,500 ft below the requirement for VFR: Minimum altitudes (2011), and 3,000 ft below the published off-route obstruction clearance altitude.

The airplane was equipped with VOR and GPS navigation equipment, but the type and capability were not specified. The report also did not mention whether the airplane was equipped with an autopilot system. Inspections of the wreckage found only crash-related damage to the airplane’s systems. Fuel was detected at the site and inside the fuel pump. Autopsies determined the pilot and passenger both died in the crash and both tested negative for drugs and alcohol (NTSB, 2013).

The Airline

Great Lakes Air is a part 135 air taxi service based in St. Ignace, Michigan (NTSB, 2013, p. 2). It could be easily confused with Great Lakes Aviation DBA Great Lakes Airlines, a part 121 regional airline based in Cheyenne, Wyoming (FAA, 2013). Great Lakes Air and Great Lakes Aviation both have NTSB accident database records dated 3 December 2011.

Applying Reason’s Model

Keeping in mind that the cause of the accident has not been determined officially, the following facts can be drawn from the recent accident report for academic purposes.

- Organizational Influences: Lack of vigilant adherence to regulations and airline procedures.

- Unsafe Supervision: Dispatch responsibilities were delegated to pilots.

- Preconditions for Unsafe Acts: Co-worker told the pilot and passenger that the weather had improved.

- Unsafe Acts: Pilot failed to become familiar with all information pertinent to the flight, and continued VFR flight into IMC.

References

- Bad weather cited in crash that killed Amazon exec. (2013, March 10). Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved from http://host.madison.com/travel/national/bad-weather-cited-in-crash-that-killed-amazon-exec/article_48f91efd-b73e-507d-81b7-7326b9f3dee7.html

- Basic VFR weather minimums, 14 C.F.R. § 91.155 (2011).

- Federal Aviation Administration. (2004). Airplane flying handbook. Retrieved from https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aircraft/airplane_handbook/media/FAA-H-8083-3B.pdf

- Federal Aviation Administration. (2013). Airline certificate information [Data set]. Retrieved from http://av-info.faa.gov/OpCert.asp

- Great Lakes Air. (2000). General operations manual. [Excerpts]. NTSB docket management system (Accident ID CEN12FA097, Document 9). Retrieved from http://dms.ntsb.gov/pubdms/search/

- Mackinac Bridge Authority. (2012, January 3). [Photograph of the Mackinac Bridge]. In Internet Archive. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20120103135145im_/http://cam.mackinacbridge.org/fullsize4.jpg

- Michigan Department of State Police. (2011). Original incident report. NTSB docket management system (Accident ID CEN12FA097, Document 7). Retrieved from http://dms.ntsb.gov/pubdms/search/

- Michigan Department of Transportation. (2013). Michigan aeronautical chart.

- Miles, G. (2013, March 10). Report: Weather poor at time of Mich. plane crash that killed exec. The Detroit News. Retrieved from http://www.detroitnews.com/article/20130310/METRO/303100307

- National Transportation Safety Board. (2011). Record of interviews. NTSB docket management system (Accident ID CEN12FA097, Document 1). Retrieved from http://dms.ntsb.gov/pubdms/search/

- National Transportation Safety Board. (2013). Factual report aviation. Aviation accident database (NTSB No. CEN12FA097). Retrieved from http://www.ntsb.gov/aviationquery/

- Preflight action, 14 C.F.R. § 91.103 (2011).

- VFR: Minimum altitudes, 14 C.F.R. § 135.203 (2011).

- VFR: Visibility requirements, 14 C.F.R. § 135.205 (2011).

- Weather reports and forecasts, 14 C.F.R. § 135.213 (2011).

One response to “St. Ignace Fatal Flight of Amazon.com Exec”

I am a retired airline pilot with 28000 accident free hours. I flew for Great Lakes Air shortly after retirement in the summer of 2007. Single pilot part 135 VFR charter flying demands sound judgement and solid instrument flying skills when flying at night in marginal VFR conditions. Ultimately it is the responsibility of the pilot to determine if wx conditions are suitable for conducting both legal and safe flight operations. It was my experience that no pilot’s judgement was ever questioned if they chose not to fly in marginal weather conditions. Thank you for a well written and researched article